Will Vinson on Unlocking Creativity Through Rhythmic Strength

Let’s begin with a simple thought experiment: There are two tenor players sitting in at a straight-ahead jam session. Player 1 has a great sound, solid command of the harmony, superb chops, a fulsome and controlled altissimo, creative ideas, but a tendency to rush the time. Player 2 has an average sound, a limited grasp of harmony, mediocre chops, a standard range, but the time feels great. Who would you rather listen to? I know my answer. To put it with brutal simplicity: all of the amazing ideas you have are only as good as the time with which you deliver them.

The words “time” and “rhythm” are often used somewhat carelessly and interchangeably. They do not mean the same thing. Time is what lies beneath everything we play. It includes the stability of the beat and also the way we make the beat feel. Rhythm, meanwhile, refers to the choices we make about what to do with time. One possible analogy you could draw would be the difference between language and narrative – Everyone wants to tell a good story, but if you don’t have a good command of the language you’re telling it in, it won’t cut through. The same goes for time and rhythm. Trying to deliver creative rhythmic choices without a strong foundation in time will fatally undermine those choices, quite possibly leading you to avoid continuing to make them.

And just consider for a minute how important rhythm is.

In my first book, Sideways: a Horizontal Concept of Harmony for the Jazz Soloist, I made the case that harmony should be seen in essence as deriving from melody, and that the two are essentially different expressions of the same thing. In my book, Time On Your Side: Unlocking Creativity Through Rhythmic Strength, I raise the question: what is melody without rhythm? There are many ways to answer that, I suppose, but the simplest one is this: melody without rhythm is… not melody. And yet many of us, without realizing it, are downplaying the importance of both time and rhythm to melody in the way we improvise. We downplay time when we neglect it in our practice regime. Downstream of that, our focus, in the moment of improvising, is on note choices and on how we accurately and creatively work with the harmony of a tune. These decisions take so much of our brainpower that there’s not much left to spare. As a result, the level of variation in pitch choice (scales, patterns, extensions, superimpositions) drastically outperforms that of rhythm (lots and lots of consecutive 8th notes and, depending on the tempo, 16th notes). When we consider that jazz is a form of music with a character so deeply defined by rhythm, this seems borderline absurd.

Over the course of my career I’ve worked with literally hundreds of horn-playing students and many of them have had the same issues caused by underdeveloped time wreaking havoc across all other areas of their playing. Very often they are aware of this, but they don’t know what to do about it. They know they should be practicing with a metronome, but they’re often very confused about how to use it. Should they switch it on and just play normally (doesn’t hurt, but doesn’t necessarily help that much). Or should they be setting it to click on the second 16th note quintuplet of the 4th beat in every 7th bar (you’d be surprised how often something like that comes up, and I can pretty confidently tell you that, if you’re struggling with your time feel, this kind of thing will do nothing but put you further inside your own head and drive you crazy)? In Time On Your Side, I offer a comprehensive and detailed account of all of the things that have helped me fortify my relationship with both time and rhythm. I can say with near certainty that practicing the material will make you a stronger player where time is concerned (even if you don’t make it past Exercise 1). And, since I would argue that good time directly correlates to higher levels of confidence and projection of authority, that means you’ll benefit from an upward spiral and be a better player across the board.

Time is natural. We feel it in our bodies, when it’s good and when it’s bad. But it doesn’t come naturally. This is actually good news: if your time is letting you down, the problem is not inherent to you, and can be fixed. My goal in teaching this topic is to encourage musicians to examine the impact that their weaknesses in time, time-feel, and rhythm, have on every aspect of their playing. Once they’ve done that, I make it my job to provide them with a plethora of exercises and approaches they can apply to their playing which hopefully will last them a lifetime.

Time is More Than Just Time

When your time is substandard, you will have more of a tendency toward repetitive use of single note values, most commonly the 8th note. If you can simulate a good time-feel, or at the very least prevent yourself from turning the beat around, using constant lines of 8th notes, any rhythmic variation will heighten the risk that your time-feel will lose its precarious balance and your weaknesses will be revealed. It’s no wonder that players want to avoid that risk. But just think for a moment about the implications of this in improvised music making. What are the truisms about jazz that even the uninitiated know? It’s about freedom, taking risks, searching. There’s a paradox in there: many musicians take that freedom and use it to avoid taking risks and steer clear of uncharted territory. Sometimes, I suppose, this could be because of a fundamental lack of creativity. But a much more ubiquitous cause is, in my experience, the fear of exposing a poor command of time. And, as I evoked in the opening paragraph, a poor command of time is apparent to all listeners. You can’t hide from it, and it undermines everything.

When you have to be physically connected to a continuous note-value in order to stand a chance of playing with good time, it leads not only to monotony, but also to two other problems which are something of an epidemic in horn players:

- Overplaying. How often do you finish a solo and say to yourself: “that wasn’t bad. I just wish I’d played a few more notes.” Silly question, right? It never happens. The opposite, on the other hand, happens a lot. Often, the horn player’s answer to this is just to promise themselves they’ll play less on the next solo. But what if the overplaying isn’t merely an aesthetic choice? What if it happens as a result of the need to keep playing those 8th notes in order to stay in the pocket? Start slowing down your ideas and introducing space and what happens? You lose your footing in the time.Most common (and worst) remedy? Fill up all the space with repetitive note values in order to stay physically connected with the time.

- Obfuscation. Jazz has a reputation among some non-musicians for being overly complicated and pretentious. It’s not fair to tar the giants of this music with that brush, but it’s less unfair when it comes to a large segment of, particularly less experienced, musicians. Partly this is due to an egotistical urge: to display to people that you know how to execute the hippest ideas and that you are in command of some really complex language. But, in my opinion, there’s a more common cause: if you play something simple, then most listeners have a good chance of understanding what it is that you’re playing. And if they know what you’re playing, then they can tell how well you’re playing it. It is my firm belief that if a rhythmically simple, comprehensible, digestible idea is being executed with bad time, there’s no covering it up.Most common (and even worse) remedy: play something needlessly complex, so that a) you distract from your weaknesses and b) no one will be able to decipher what it is you’re playing so they won’t know how well you’re playing it. The question of why you’re playing it will go tragically unanswered in the listener’s mind.

- Poor phrasing. One of the joys of being a horn player is the potential you have for creative phrasing of melodies, both improvised and composed. Several elements go into phrasing: timbre, pitch, dynamics and, crucially, time. Personally, I like to try to evoke the kinds of temporal pushes and pulls for which my favorite singers, from Billie Holiday to João Gilberto to Björk, are famous. As natural as these phrasing idiosyncrasies sound to the listener, they are in fact the product of great sophistication. In order to manipulate time to give the impression of temporal elasticity, perhaps recalling the way we do so in speech, you need to have an even more solid sense of the underlying foundation of time than you would otherwise. The point of elastic is that it always snaps back. You don’t want to become the musical equivalent of the worn-out waistband on a pair of old sweat pants.Most common symptom: playing the melody in a robotic way, or filling the spaces between phrases with mindless noodling.

I think most people sense that overplaying, obfuscation and awkward phrasing are problems in their playing. But trying to fix them by just promising themselves they’ll do it less is a bit like trying to solve climate change by building a giant air conditioner over the Arctic. The remedy ignores and even exacerbates the nature of the problem.

Time All the Time

Many people are familiar with the “10,000-hour rule”, famously referenced by Malcolm Gladwell in his 2008 book, Outliers. Spend that amount of time working on a craft, the rule has it, and you will basically master it. Whether or not it’s true, it certainly is true that if you don’t put in the time on your instrument, you stand a slimmer chance of fulfilling anything approaching your potential. There’s a limit to the amount of time you can actually spend playing your instrument, however. There are other things that need to be done in life – brushing your teeth, cooking, commuting, day job, childcare – you name it. Well, the great thing about time is that you can practice it in literally any situation. There’s no need to have your instrument anywhere near you. I think it’s fair to say that only half of my practice time actually takes place at the horn. So that 10,000 hours just became 20,000. Take that, Gladwell!

At least half of the exercises in Time On Your Side can be practiced by tapping your hands on your knees, or even your fingers on a steering wheel. In fact, it’s arguably better, once you have the hang of some of this stuff, to be doing something else as well to keep your mind occupied. When we’re practicing we’re often looking for and expecting intellectual stimulation. Rhythm can of course give you that. But when it comes to the deep internalization of some things that your mind has already worked out, the key is physical repetition, and the worst thing that can happen is that you get bored and stop repeating, in search of another shiny (and usually more complex) object to fixate on.

The Power and Purpose of Muscle Memory

A few years ago, I co-led a masterclass with Eric Harland, the master jazz drummer. He said something which has, despite its simplicity (most great ideas seem obvious once you’ve been introduced to them), stuck with me and will no doubt continue to do so. I paraphrase:

Don’t fool yourself into believing that, just because you understand something, you can do it.

So many of the ideas and approaches that we tackle in our development as musicians in this incredibly complex and wonderful artform are things that require a lot of brain-power to understand. And in those cases it’s largely in the understanding that the work lies. This is something to which we jazz musicians, and especially non-rhythm section players, are very accustomed.

There are, of course, plenty of rhythmic ideas you could have that require some intellectual understanding to be able to master. But time itself is much more of a physical phenomenon. It doesn’t take a degree in quantum physics to work out what a quarter-note is. But the Achilles’ heel of the horn player is to assume that, since it’s not a complex principle, it must therefore be easy and, as a result, pointless to spend a lot of time over. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Time On Your Side contains 40 exercises for developing both time-feel and rhythmic resilience. Some of them are quite involved and detailed. I’m going to share one of them, exercise 19, below.

In the book, I explain all the different ways you should practice the material (on/away from your instrument, tapping/not tapping your foot and other parameters). Right now, I’m going to give you a sample exercise from the book, which addresses rhythmic independence through the use of odd-time claves, tapped or clapped alongside melodies in a specific time signature, in this case 4/4.

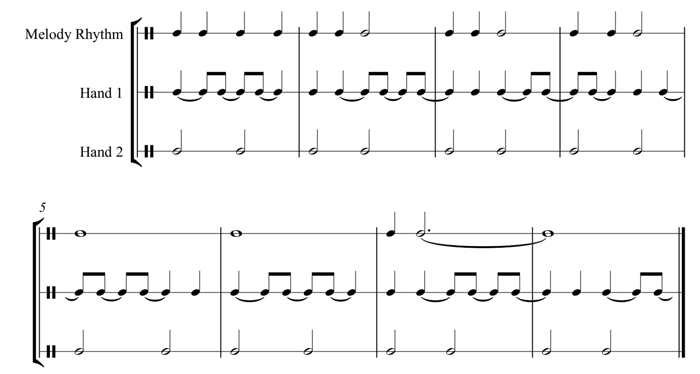

The two rhythms below are based on subdividing a group of five 8th notes into, firstly a 2 and 3, and then a 3 and a 2, to produce a 5/8 clave. Essentially these are the same rhythm, just starting in a different place. Clap the clave in one hand, while clapping a consistent expression of the underlying meter in the other:

2 then 3:

3 then 2:

Since both of them take a 5-bar cycle (completed above) of 4/4 to resolve, they will put both the 2 and the 3 side of the rhythm in every possible position within a bar during that 5-bar cycle.

Pick one of these (or you can do both) and begin by counting the beats of the bar aloud as you clap the rhythm. Then sing some increasingly complex melodies with them. The examples below use the 3 -2 formulation, but you should try it both ways.

5/8 clave with the melody to “Bye Bye Blackbird”:

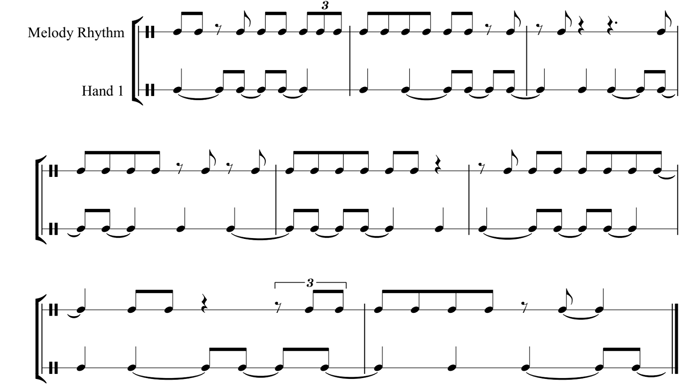

5/8 clave with the melody to Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation”:

You’ll notice that, in the last example, I left out “Hand 2”, to save space. You should still clap that note value, and perhaps also move it to beats 2 and 4 of the bar, for variation. As you start to loosen up, you’ll be able to notice the resolution on every 5th bar. So, when singing a tune with 4-bar phrases, you’ll hear the beginning of the pattern on bar 1 of the first phrase, bar 2 of the second, 3 of the third, and so on.

Sometimes it feels as though, in music-making, our job is to balance two competing parts of our brain: creativity on one side, and muscle memory on the other. You can’t very effectively be creative in the moment of performance if you have to keep reminding yourself where the key for C natural is on your instrument. Muscle memory takes care of that. We have all of the bebop scales, arpeggios and a bunch of patterns and licks at our disposal, ready to be delivered without hesitation.

Conversely and unfortunately, you can emphasize muscle memory and de-emphasize creativity when you play music and just about get away with it. Sometimes it’s hard not to: the mental demands on an improvising musician are pretty intense, and some of it needs to be delegated to our fingers. The key is to work out which parts of our playing to delegate and which to maintain control over. It’s all too common to get this wrong. The last place I want to be when I’m soloing is to be mindlessly playing scales while thinking about time-feel. If I have to think about my time-feel while I’m playing an 8th note line, the chances are it’s not going to be a great feel. No, I want to be thinking about the unique content of what I’m playing: the melodic shape, the harmonic nuance, and of course the rhythmic ideas themselves.

I can only really do that if I know that, underneath it all, I have a solid foundation of time on my side.

All music happens in time. But Jazz in particular is, more than most western forms that came before it, a rhythm music. As a result, time and rhythm are paramount for the jazz artist. You can learn as many fancy tricks of technique and theory as you like – to put it bluntly, if you can’t deliver them with good time, they are all for nothing. Unlike rhythm section players, saxophonists are often preoccupied with the shiny objects they can produce on this incredibly expressive and dexterous instrument.

But this tendency routinely overtakes their connection with the most fundamental element of all. In Time On Your Side: Unlocking Creativity Through Rhythmic Strength, Will Vinson details all of the things he’s done to redress this balance and to put time on his side and, in so doing, to elevate every other aspect of his playing and let those shiny objects shine brighter!