Demystifying the Art of Arranging for Saxophone Quartet

Introduction

If you’ve ever had any interest in creating arrangements for saxophone quartet, or if you’re simply curious about how those arrangements are created, the read on, as there are few people walking the planet would be as qualified on the subject as the man you’re about to hear from.

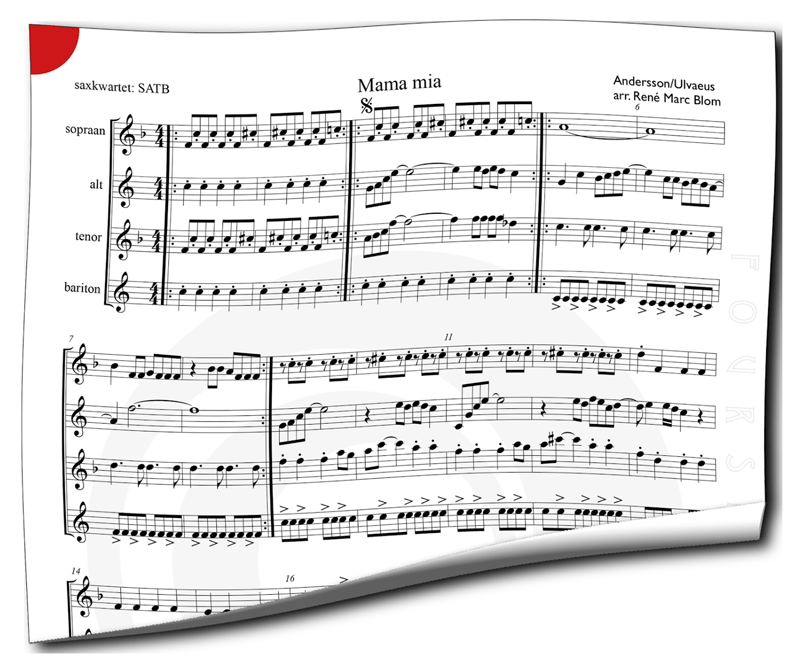

René Blom is a conservatory-trained saxophonist and prolific arranger of saxophone quartets, with roughly 250 arrangements in a wide variety of styles under his belt at the time of this article’s publication.

Interview

Best. Saxophone. Website. Ever.: Can any song be turned into a saxophone arrangement?

René Blom: Well, to arrange an existing piece of music for a saxophone quartet, you must first decide whether the existing piece – preferably the original and not a cover – is suitable. A choral work that was written for a four-part choir is of course perfect, but an orchestral work that has a large number of independent melodic parts for the woodwind, brass, and string section would quickly become very difficult. Another example would be pop songs that rely on a prominent rhythm section are tough to transform into four winds.

BSWE: Not every original piece is four-part, of course…

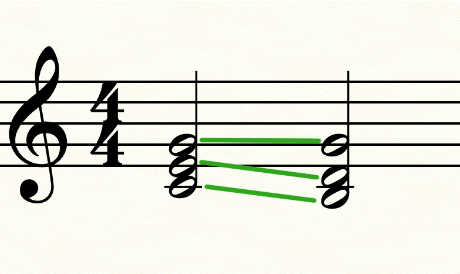

RB: Indeed, which is why music containing complex chords, as is the case with jazz music or 20th century classical music, for example, can be a challenge and at times simply impossible. When a triad is used, it is easy to transform that into 4 saxophones: fundamental, third, fifth, and an extra of one of these in the fourth saxophone part.

A 7th chord is not tricky either, as you have exactly 4 tones: fundamental, third, fifth and seventh. But what to do with a 9th or 11th chord?

Here it is often possible to leave out the “least important” tones. The fundamental can never be missing, nor can the third, since it’s the third which determines major or minor. The seventh, ninth, or eleventh cannot be left out either, of course, as they are quite crucial in establishing authentic-sounding jazz harmony.

The fifth can often be left out. But sometimes the fifth is part of the melody, and then it gets really tricky…

BSWE: Is the distribution of chord tones the hardest part to work out?

RB: Well, once you’ve decided on a suitable song or piece of music for your arrangement, classical music theory becomes very handy in “knitting” those chord tones together. As I said earlier, in a triad, one of the three notes in the triad gets doubled. However, most often it’s not the third.

Another general concept to master when moving from one triad to another is that any chord tone common to both chords is often sustained in the same “voice” or part as much as possible. An example would be a C major chord, C-E-G, followed by a G major chord, G-B-D. In this case, the G is sustained and so the two remaining tones change into the, ideally, nearest chord tones of the C major chord.

The example above is one of the most basic rules of harmonic theory, but there are many more. Fortunately, one can find some fantastic books to delve deeper into this matter.

BSWE: Will the final arrangements still resemble the original though?

Mostly. Another challenge in the arranging process, of course, is when you want to arrange for a “not-quite-sax-like” instrument with one of the saxophones. A string quartet also plays four notes simultaneously, but it has a very different character with regards to the attack of the tone. With a string instrument, the tone swells naturally because of the bow whereas with a saxophone, you need to do this consciously with breath support, embouchure, etc.

Fortunately, we as listeners have a tendency to hear music as it sounded when we first heard it, even if what we’re actually hearing is not a complete representation of the original! It’s like our brain “fills in the blanks.”

When you have heard a certain piece of music or a popular song many times, a decent sax quartet arrangement will, for the most part, give you the experience of listening to the original. Your brain fills in the instruments and sounds which the saxophones cannot or do not play. Of course, it is always helpful when saxophonists can really get into their parts and as make a concerted effort to reproduce the sound and feeling of the instrument that they’re tasked with imitating.

BSWE: Do you generally stick to the instrumentation of soprano, alto, tenor, and baritone, or are there times that you use a different combination of saxophones? And if you do change the instrumentation, how do you arrive at that decision?

In most cases, I use the four different saxophones – soprano, alto, tenor, and baritone. I sometimes swap the soprano for a second alto because the soprano has a slightly more “classical” sound than the alto.

An example of when I used this instrumentation was on my arrangement of “A Foggy Day.” Although this is the arrangement that is offered on my website, I can replace the first alto with a soprano if desired. Sometimes this means that I have to change the key, as the soprano cannot play as low. Consequently, when one of the other saxophones ends up too high, a problem may arise that makes it impossible or forces me to change one or more parts to keep within their range. This depends on the song.

BSWE: Following up on the previous question, do you have any guidelines you follow in terms of choosing the predominant register for each individual saxophone part, or do you generally stick to the comfortable register of each instrument and allow the difference in each instrument’s natural range to make for a full-sounding arrangement?

RB: I always try to prevent having to play very low or very high notes. An exception is the low Bb (or A) for the baritone, as it is characteristic of this “basic bass” instrument and the baritone players are used to it. But especially with sopranos I would never do that.

I keep the same thing in mind with high notes. My intention is to never go higher than a high D. Unless the part incidentally reaches this height, as with Mozart’s “Lacrimosa”, or “Sir Duke” by Stevie Wonder, where both altos play a high E a couple of times. But I would not write long passages in the highest register.

BSWE: How much time do you spend arranging?

RB: Since my aim is to make a new arrangement every week, I spend most of my time arranging for my website, foursaxes.com. Before posting an arrangement on the website, however, I preview it “in real life” with a saxophone quartet, which generally results in a few necessary adjustments here and there.

I also need to make an MP3 file of the arrangement. It is always a challenge to make it sound as natural as possible with my music software, but I assume most musicians can hear past the artificiality of the digital saxophones with the understanding that this is simply for demonstration purposes.

Special offer during the months of March and April!

When purchasing an arrangement from FourSaxes.com, use the password SPRING24 and choose an additional arrangement for free.

To get the discount, go to FourSaxes.com and select one or more arrangements. At checkout, enter into the “Remarks” box the discount code, SPRING24 and after the code the name of the free arrangement you want to receive. (For example: SPRING24: Flintstones SATB)